When it comes to solid waste management, Professor Maria Antonia N. Tanchuling likes to look at the issue taking into account their strong social factors. She sees that the two things are intertwined, especially in her home country of The Philippines, where waste management cannot be separated from the issues like informal workers, waste-pickers, and massive sachet consumption.

‘Everything comes in sachets, like shampoo, cooking oil, soy sauce. When we do the survey, we are surprised that people buy cooking oil by sachet. But that gives you an idea of the very low purchasing power of the people,’ she said in a recent interview with Regional Knowledge Centre for Marine Plastic Debris (RKC-MPD).

Teaching at the Institute of Civil Engineering at the University of the Philippines in Manila, Professor Tanchuling has done a lot of research on plastic waste management, including microplastics. Her dissertation topic was on contaminants transported underneath the landfill clay liners, which led her to study the biggest dumpsite in The Philippines at that time, the Payatas in Metro Manila.

‘To fully understand what goes into the dumpsite, especially with the landfill liners or the contaminant transport, I looked at the upstream side, so that’s how I got interested in solid waste management,’ she said.

At this occassion, Professor Tanchuling discussed a great length topics such as the importance of data availability and where the funding should go for the sustainability of plastic waste management. Below are the excerpts of the interview.

RKC-MPD ERIA: You recently mentioned how the problem with regard to plastic is new. What makes it new? Why the issue only emerged recently?

Prof Maria Antonia Tanchuling: I think it’s the report written by Jenna Jambeck citing The Philippines as the third largest contributor of plastics to the oceans. Because of that, a lot of funds were allocated for it…(along with) a lot of pressure to work on this issue. And then they looked for a representative from The Philippines to be trained on microplastics. I was nominated, I think that was in 2015, 2016. This was the first time I learned about microplastic. From that training, I started doing research on microplastics because no one at that time that I knew of was doing anything about microplastics in The Philippines.

Prof Maria Antonia Tanchuling working in the laboratorium. (Photo Courtesy of Prof Tanchuling)

You conducted some research about the existence of plastic in several rivers in Manila River Mouths. What kind of plastic that mostly found in the rivers in Manila or in The Philippines? And what do you think to be the driving factors behind that?

A lot of items collected in the rivers are plastic bags, the single-use carrier bags that are given in grocery stores, we have a lot of those. A lot of sachets too. Sachet is something that you would expect from a developing country because that’s what is affordable, but even compared to other developing countries, we have more consumption of sachets.

We also have PET bottles. Although in terms of the plastics that are being recycled, it’s only the rigid plastics, like the PET bottles and the high-density polyethylene, but there’s really not enough recycling infrastructure that even these valuable rigid plastics you can still find in rivers, in bodies of water.

In terms of microplastics, I think there’s only one river mouth in which we sampled primary microplastics in the form of beads, and that’s where the plastic manufacturers are. But the most common ones in almost all the rivers that we surveyed, you see fragments of bigger plastic items, especially shopping bags. You can also observe filaments, or like fibre lines, which we assume to be coming from laundry wastewater, through sewage.

We’ve also made studies on microplastics from sewage treatment plants. And we see a lot of these microplastics in the shape of fibres. In areas where there is fishing, we also see this fibre shape coming from fish nets.

Very few research mentioning about microplastic—where were they actually derived from and how could they end up. People in general probably didn’t know where the microplastic comes from and how it can be formed. Is it naturally or mechanically-formed? How could they end up in the rivers in Metro Manila?

Because we see a lot of the fragments, these are really coming from the macroplastics in the river. There is a problem with waste management because wastes are directly dumped into the river. As time goes by, plastic items get fragmented slowly by UV radiation, mechanical abrasion, and other natural processes.

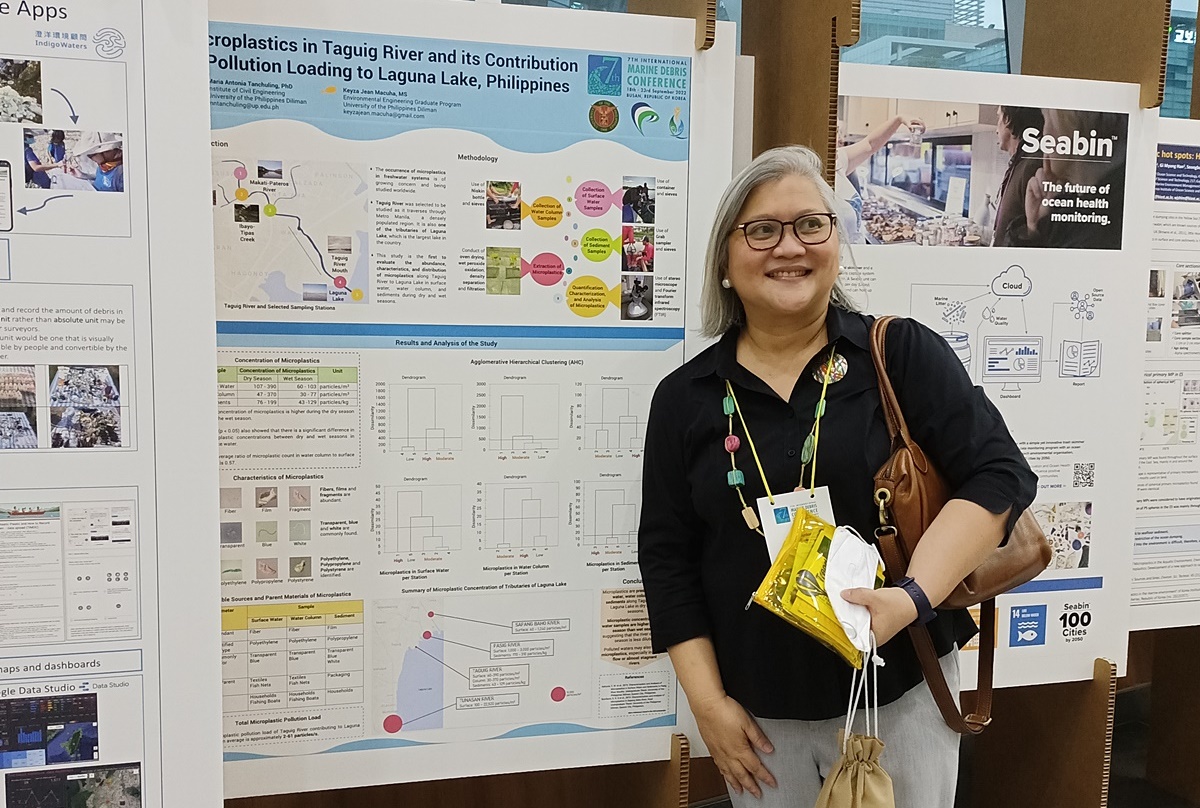

Prof Tanchuling in front of one of her research posters. (Photo Courtesy of Prof Tanchuling)

And then as I have mentioned, some also can come from our laundry wastewater. From the studies in sewage treatment plants, we understood that the conventional treatment system, like activated sludge, can remove around 85 percent of the microplastics. But you still have 15 percent that is left untreated and a large portion of the population is not served by a sewage treatment plant. So, if you discharge your sewage directly, you can still have those (plastic) fibres. I think that’s the main source.

As I’ve mentioned the beads, the primary microplastics found in the river was of much smaller proportion. But that can come from leakage from plastic factories, or cosmetics items such as facial wash. But we did not see a lot of them in sewage treatment plants. It’s minimal compared to secondary microplastics. I would say the main cause really is the poor waste management of solid waste.

Since you also study both microplastic and macroplastic, which one according to you is more harmful to the environment, including marine environment?

Both of them would be hazardous, but I think microplastics are more problematic because the smaller organisms can ingest them, and they would be able to enter the food chain until humans can consume them. While the bigger plastics can kill the animals because they mistake it for food, leaving the animals malnourished. So both (plastic types) are harmful in that sense.

Are there any findings that you found surprising when doing your research?

No, because visually I can see how much plastics are there in the river, so it wasn’t very surprising to see the results. Maybe what surprised me more was the lack of waste management capacity of the local government, simple things like the lack of data.

We look at the waste management systems of local government units, using the tools developed by UN-Habitat and the University of Leeds. We have been really advocating for the local government units to quantify and establish a clear picture of the value chain of their waste. How much waste is being generated, how much waste is being disposed, and how much waste is being recycled? So even those, the quality, the level of data collection is very poor.

They don’t (even) have weighing scales at many disposal sites. They just estimate (the quantity) by the number of trucks, and make assumptions on the density. Some are overloaded, some are under-loaded. We try to digitalize waste leakage data and manage it through a computer system. Currently, leakage data is not digitalized and reported. This is the reason recycling rates can also be erroneous and overestimated.

As long as the data is not digitally managed, we really cannot solve the problem of waste leakage. We blame the people for not being disciplined, and for throwing garbage in the river. But in many places, people keep on throwing because they do not have adequate infrastructure for waste collection.

Collection is not enough. In many areas of the country, there is no collection of waste, they just leave it up to the barangays (village), to the local government units. But the local government units are also not well-capacitated. So the problem is really in the infrastructure of waste management.

Prof Tanchuling with her colleagues at a landfill. (Photo Courtesy of Prof Tanchuling)

We really cannot improve if we do not admit that something is wrong with the waste management infrastructure itself. So, to tackle the source of the problem, we need to work on the policy, by preparing all this data and advocating for a good information system that is publicly available to make data transparent. I think you’re all familiar with how corrupt our government can be. And one way of tackling corruption is by making data transparent. That’s why a lot of corrupt politicians do not like this.

Does the government put waste management as the top priority of their agenda and give enough funding?

I don’t think there’s enough funding given. There are no fees for waste management. The waste management system is heavily funded by the government, and there is no participation from the private sector, except if you’re a commercial establishment. There are not enough funds to sustainably operate solid waste management systems.

So that is one of the reasons why we are also pushing for more funds to be used for collection and recycling of plastics. We just passed the Extended Producers Responsibility (EPR) in July 2022. And the IRR, the Implementing Rules and Regulations, is now being prepared.

Do you think that there will be a lot of companies interested to be involved in the EPR?

The multinationals, the bigger companies are interested. And in fact, in a way, they’re more advanced. They have started to manage the waste on their own. The bigger companies, I think, are interested because they’re driven by their mother companies. They have these commitments to sustainability. And that also makes good business sense.

Do you think there are enough regulations for waste management in The Philippines?

Yes, I would say regulation-wise, it is adequate. But really, the problem is the enforcement of the law. How do we really improve enforcement?

But the society itself, are people aware of this issue?

Yes, they are. Environmental education is included in the curriculum at all levels, from primary, high school, and tertiary levels. But again, I would say it’s not enough to keep on educating our population if the infrastructure is not present. For example, if you ask people, ‘Why don’t you segregate your waste?’ They would say that they see the garbage collectors mixing them anyway. But the garbage collectors mix them because the segregated wastes have no designated places to go. We do not have the facilities.

That’s why I would really say the infrastructure is lacking. Even for the high-value plastics, it’s only in the highly urbanized cities that you find collection centres. The Philippines is an archipelago, so you would imagine how it is on the island.

Are there a lot of recycling companies in The Philippines? Are they still receiving a lot of waste from other countries as well until now?

According to our estimation, only 9 percent of the post-consumer plastic waste get recycled locally. First, there aren’t a lot of recycling plants. What we have are collection points or junk shops. We have the waste-pickers who go from house to house, collecting your waste, and then it goes to a junk shop, and then the junk shops sell it to consolidators. Those consolidators are just physically consolidating plastic waste materials, or compresses them into compact and tight bales. The recyclers would melt them and make them into recycled plastic products. But most of the plastics get pelletised and sent mostly to China. These recyclers also get the imported waste plastic

Plastic waste has emerged as an important environmental concern relatively recently. In this emerging field of study have you experienced any gender gap reflected for example on the number of female researchers, or do you see an equitable female representation in the plastic waste management sphere? And from your perspective, are there any specific challenges you have faced as a female researcher working on the topic of plastic, marine plastic, microplastic?

I don’t have the numbers regarding the participation of women in the research field but I don’t see any gap. Maybe that’s only specific to The Philippines, because, for example, in the UP College of Engineering, half of the population is female. I think compared to other countries, we have more women participation. We don’t see a lot of bias or prejudice against women. Especially, maybe in the field of environmental engineering, relatively, you see a lot of women researchers. And maybe if you go to construction engineering, or maybe civil engineering, geo-technical engineering, those are more or less male-dominated fields.

Within the plastic waste management sphere, I know empirically that many women work as informal waste collectors, in the informal economy. Also, on small community-based efforts to recycle waste, you see a strong female representation.

Prof Tanchuling with fellow women colleagues working on waste issues. (Photo Courtesy of Prof Tanchuling)

When you mention about the informal waste workers that are mostly women, do you think they are more vulnerable to being harmed by the plastic waste?

Yes, because when they are childbearing, they can be impacted more, health-wise. And of course, all the other associated problems regarding women, like having double tasks, when they go home, they also do the house chores.

According to the news, the Republic of Korea just committed US$7 million to the Philippines to help combat marine plastics. This year, they plan to provide a marine litter-collecting vessel to Manila Bay. What do you think the country will benefit from this activity?

Maybe it’s good to be able to clean up the ocean, but I don’t think it’s sustainable. We cannot keep on doing it forever. There should come a point where we should stop the source upstream.

In fact, it’s not only in South Korea. There are so many proposals that are coming into wanting to clean up the plastics that are out there. Maybe it’s a solution now, but we should do something really upstream. Starting from how to reduce the amount of plastics that are being generated. And again, the infrastructure for waste management. I think those are sustainable solutions.

Some of the funding provided to tackle waste management are not very effective. What are your key takeaways about this topic?

I would always say that regarding the data, we should have policies that are based on evidence. It should be evidence-based, it’s data-driven. And then next, we should really improve our waste management infrastructure. Just simply improving collection coverage will decrease the amount of leakage of plastics into the environment.

Prof Tanchuling at a river cleanup system by The Ocean Clean Up. (Photo Courtesy of Prof Tanchuling)

I think if citizens are more vigilant, they can also demand more especially from their local executives. Many local executives, especially the young ones, are also open. So, we should also start working with them. But to be vigilant, the citizens also need the data, they need the information.

Even with my students, I ask them, ‘Do you know where your waste goes to?’ Not a lot of people would know. Same with wastewater. I think wastewater is even more difficult. ‘When you flush the toilet, do you know where your wastewater goes?’ From the side of being an academic, our contribution is to ensure that we build on the data we share. And what you (RKC-MPD) are doing is good. What we (researchers) do, the general public should know and understand, and appreciate.